U.S. President

Donald Trump

is privately musing about exiting the North American trade pact, people familiar with the matter said, injecting further uncertainty about the deal’s future into pivotal renegotiations involving the United States, Canada and Mexico.

The president has asked aides why he shouldn’t withdraw from the agreement, which he signed during his first term, though he has stopped short of flatly signalling that he will do so, according to the people who spoke on condition of anonymity to describe internal discussions.

A White House official, asked about the discussions, described Trump as the ultimate decision-maker and someone always seeking a better deal for the American people. Discussion about potential action amounted to baseless speculation before an announcement from the president, the official said.

An official in U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer’s office said that a rubber-stamp of the 2019 terms was not in the national interest and the administration intended to keep Trump’s options open and negotiate to address issues that had been identified.

Both officials spoke on the condition of anonymity and declined to directly address whether Trump was musing about an exit from the trade pact. Greer said Tuesday that the administration would hold separate talks with Mexico and Canada, arguing that trade ties with Canada are more strained. He did not say whether Trump would approve an extension.

“Generally speaking, these negotiations are going to proceed bilaterally and separately, the Mexicans are being quite pragmatic right now. We’ve had a lot of discussions with them. With the Canadians, it’s more challenging,” Greer said on Fox Business.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum on Wednesday downplayed the likelihood that Trump would withdraw the U.S. from the deal.

“We don’t believe it, and it has never been said in the calls, because it is very important to them,” Sheinbaum said during her daily press conference when asked about the Bloomberg News story.

Canadian Prime Minister

Mark Carney

said Tuesday he had a “positive” conversation with Trump that included talk about the

Canada-United-States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA)

review, though he didn’t elaborate on those discussions. The office of Canada’s minister for U.S. trade, Dominic LeBlanc, declined to comment on the report.

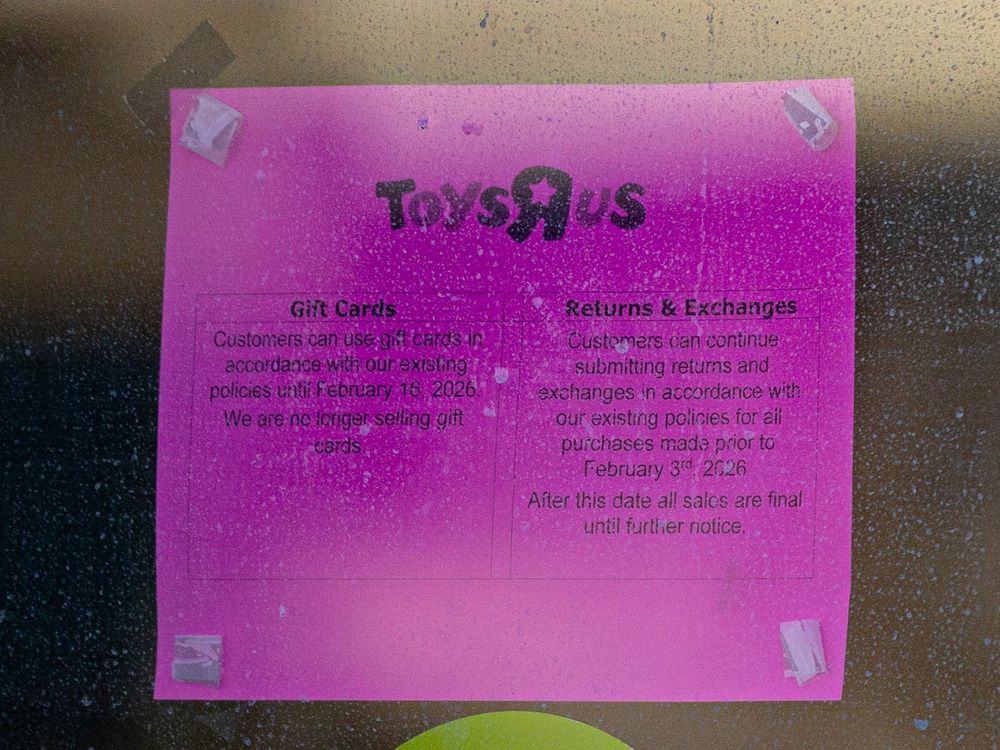

CUSMA is set for a mandatory review before a possible extension on July 1, a process that was once expected to be routine but has transformed into a contentious negotiation. Trump has demanded additional trade concessions from Ottawa and Mexico City and pressured them to address unrelated issues, including migration, drug trafficking and defence.

Greer will recommend renewal if a resolution incorporating input from industry stakeholders can be achieved, the official said, noting stronger rules of origin for key industrial goods, enhanced collaboration on critical minerals, worker protections and dumping all as areas of possible concern.

If the countries agree to a renewal, the accord would remain in force for another 16 years. But if that doesn’t happen, it could trigger annual reviews for a decade until the deal’s expiration in 2036. Any country could announce their intent to withdraw with six months’ notice.

Such a move would shake the foundations of one of the largest trading relationships in the world — the pact covers roughly US$2 trillion in goods and services — and even the threat of a U.S. departure would stoke uncertainty for investors and world leaders.

U.S. business groups and lawmakers would almost certainly rebel. The prospect of higher tariffs would also threaten to exacerbate affordability concerns heading into November’s midterm elections, in which Trump’s Republicans already face an uphill battle to keep control of Congress.

Trump routinely polls key aides on issues; the questions can be insights into what is on his mind but are far from certain in predicting his actions. It’s unclear if Trump will threaten publicly to leave or formally give the warning. It’s possible if he did so, he may use it as leverage to reach a more favourable deal rather than follow through on pulling the U.S. out of the agreement.

Trump has already started to ratchet up pressure on Canada and Mexico; he’s threatened to hike tariffs on Canadian goods to 100 per cent if the country brokers a trade deal with China, raise levies on aircraft from Canada to 50 per cent if it does not approve certain Gulfstream jets, refused to allow the opening of a new bridge linking Ontario and Michigan and vowed duties on products from Mexico and others that ship oil to Cuba.

CUSMA replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement, which controlled trade between three countries since 1994 but became a target of Trump’s ire during his first run for the White House. Trump threatened to leave NAFTA before agreeing to the new deal that tightened rules, raised US auto content requirements and included a sunset clause, which mandated this summer’s renegotiation.

Even though he negotiated the current system, Trump has soured on the North American trading relationship. During a visit to a Ford Motor Co. plant near Detroit, he called the pact “irrelevant” but stopped short of saying he would quit it. He has also floated the possibility of negotiating bilateral agreements with Canada and Mexico.

“I don’t even think about CUSMA,” he said. “I want to see Canada and Mexico do well, but the problem is we don’t need their product.”

Trump sent a different signal about the agreement last May when meeting with Carney, saying “it’s there, it’s good. We use it for certain things” and calling it “great for all countries.” But, he noted then, the 2026 renegotiation was looming “to adjust it or terminate it.”

Any U.S. exit from the CUSMA might cause immediate economic pain by exposing more Mexican and Canadian exports to higher American duties. Currently, most goods — with notable exceptions, including automobiles — traded under the agreement are exempt from Trump’s global tariffs.

As a result, Mexico and Canada have comparatively low average effective tariff rates compared to other products from major economic powers. Both countries are the US’s two largest trading partners and the top buyers of American goods, according to 2024 trade data. If exiting the pact triggers Canadian and Mexican retaliation, it could hamper his campaign pledge to boost US exports.

In the long run, the mere possibility of exiting the deal could push the three neighbours further apart and reverse a three-decade effort to integrate their supply chains.

Carney at last month’s World Economic Forum in Davos urged mid-sized countries to build new ties to resist economic coercion by aggressive superpowers, declaring the old rules-based international order a “fiction.”

The landmark speech, a thinly veiled shot at the U.S., angered Trump and helped prompt his latest string of threats against Canada.

The president’s declaration in January that North Atlantic Treaty Organization troops stayed “a little off the front lines” in Afghanistan also rankled Canadians, many of whom have boycotted American products and scrapped trips to the U.S. over Trump’s trade brinkmanship. Some 158 troops from Canada died in that conflict.

Trump’s unpredictability has kept world leaders off balance for the better part of his second term. His argument that the U.S. doesn’t need to import automobiles from Canada has served as a warning shot to an industry that is closely integrated across all three countries, as well as his moves to tariff North American steel and aluminum.

Yet he has also displayed a willingness to preserve much of the CUSMA, particularly with the exemption from his tariff regime, which grew out of warnings from the auto sector.

— With assistance from Alex Vasquez, Brian Platt and Gonzalo Soto.

Bloomberg.com

Trump privately weighs quitting CUSMA trade deal he negotiated

2026-02-11 11:54:11