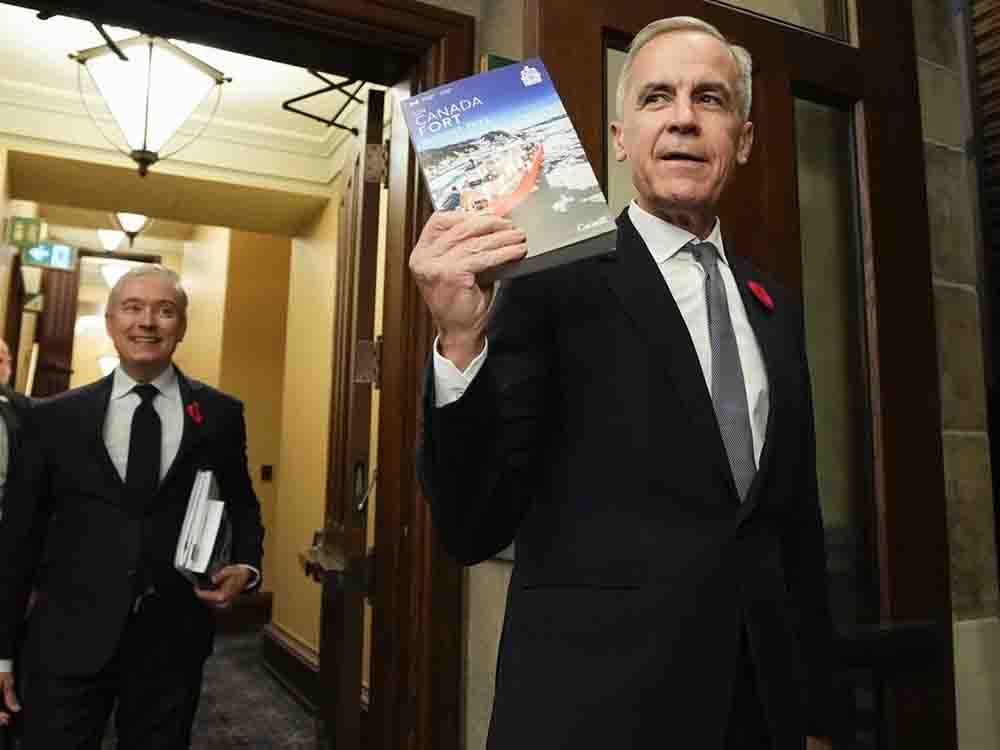

When Prime Minister

Mark Carney

‘s government tabled its

first budget

in November, it unveiled a new fiscal anchor: a reduction in the country’s deficit-to-GDP ratio going forward.

The measure left some budget watchers scratching their heads, because it isn’t often used by Canada’s Group of Seven counterparts as a fiscal guardrail, especially on its own.

“Nobody else does this,” said Mark Manger, professor of political economy and global affairs at the University of Toronto.

“Why not say you’re trying to eliminate the

deficit

, or you will have a surplus by a certain year?” he added. “That would be standard language most countries use.”

The switch from a more common declining debt-to-GDP ratio — which the Trudeau government had promised but failed to meet — as an anchor was subtle but significant: under the new rule, Canada’s indebtedness could not only grow, but grow relative to the size of the

economy

in the coming years.

“Just reducing the deficit is fine on its own, but it’s not really enough,” said Charles St-Arnaud, chief economist at Alberta Central, who described the budget’s fiscal guardrails as “weak.”

Along with a second promise to balance the newly defined operating budget within three years, Carney’s anchors have left some economists closely scrutinizing Ottawa’s finances and others warning that Canada could be on a “slippery slope” fiscally, even as the country’s

credit profile

remains in good standing for now, according to St-Arnaud.

The parliamentary budget officer (PBO) has been among the biggest skeptics. In a recent report, Jason Jacques calculated that there is only a 7.5 per cent chance the government will even achieve its target of a declining deficit-to-GDP ratio in the medium term after subjecting the anchor to a stress test. It also questioned Ottawa’s definitions of operational and capital spending, suggesting the latter was overly expansive.

During testimony in front of a parliamentary committee on Tuesday, Jacques said the federal government should require approval by the House of Commons before discarding any fiscal anchors.

“It’s a change in fiscal policy which wasn’t discussed meaningfully on Parliament Hill,” he said. “It happened without any discussion.”

Fitch Ratings Inc., meanwhile, released a post-budget report warning that Canada’s finances run the risk of “further deterioration.” Notably, Fitch looks at all levels of government when it refers to general government debt.

“A decade to 15 years before COVID, general government deficits were running around 0.5 per cent of GDP,” said Josh Grundleger, co-author of the report and sovereigns director at Fitch Ratings. “Now they’re looking around two per cent of GDP.”

Canada currently holds a AA+ rating, but its general government deficit is higher than the median of its peers in that category. Canada’s gross government debt is also projected to hit 98.5 per cent of GDP by 2027, nearly double the AA median.

Grundleger said this does not mean there is a risk of a further downgrade for Canada’s credit rating, but it does mean the agency is looking more closely at Canada’s fiscal credibility.

“It’s not convincing when you keep on changing the targets and rules, and every year there is a reason why the targets aren’t being met, and they’re being moved,” he said. “There is a growing focus from our perspective on the credibility of these tools.”

In its review of the budget, the PBO said Ottawa’s commitment to balance operational spending was dependent on how it defined the other half of its split budget approach, capital spending.

Based on the PBO’s own definition of capital spending, which does not include items such as corporate income tax expenditures, investment tax credits and operating production subsidies, which the federal government has included, Jacques said he did not think the government would reach balance in three years,

Regardless of which definition is used, Canada’s overall debt is expected to climb as the government embarks on series of investments to stimulate long-term growth in the economy. Carney’s is promising to target $500 billion in new private investment and to find $60 billion in operational savings over the next five years, with the debt-to-GDP ratio expected to remain above 43 per cent for the remainder of the decade.

St-Arnaud acknowledged the budget represented an important significant shift in focus in fiscal policy from the demand side of the economy to the supply side, with measures designed to address Canada’s

productivity

crisis.

“We are redirecting some of our attention fiscally to what actually matters,” said St-Arnaud.

“If you manage to boost your potential from a half a percentage point compared to now, that’s a lot of revenues down the road in the long-term.”

St-Arnaud said Canada may have to make these sacrifices now, in the service of more lasting economic growth.

Manger also said investments in infrastructure and major projects could yield strong results, but not every dollar of government spending will lead to a dollar of economic growth, and it’s a risk because governments don’t always know what will pay off.

He pointed to Ottawa’s sovereign

artificial intelligence fund

, which promises $925.6 million over five years to support a large-scale sovereign public AI infrastructure, as an example of an initiative that was unlikely to provide return on investment.

“Governments and civil servants are the least well-placed to decide what’s going to work in the market, and what’s going to be commercially successful and drive growth years into the future,” he said. “They have no special insight into that.”

Ultimately, Grundleger said a deficit due to productive spending is better for a credit profile versus spending that is not contributing to economic growth. Still, the federal government’s increased debt and the costs associated with serving that debt will squeeze all levels of government.

“At the federal level, if they decide to increase their tax base by taxing people to support higher debt, that just means the provinces have less room to raise taxes otherwise it starts to become crushing on people,” he said.

And unlike the European Union for example, where there is clear mechanism when a country breaks its fiscal anchors, in Canada they remain more a signal than a binding promise.

“Obviously, the British approach or the Canadian approach of saying this is what we’re going to hit, it’s more like we are exposing ourselves to public shame versus the European approach of actual penalties,” said Manger.

One silver lining to Canada’s fiscal situation, Manger said, is that the government often borrows from domestic sources.

For example, according to Finance Canada’s debt management strategy, the projected total market debt for this year is comprised of $1.293 trillion in domestic bonds, $296 billion in treasury bills and just $30 billion in foreign debt.

“We are in this absolutely fortunate position, that we are mostly borrowing from ourselves,” he said.

• Email: jgowling@postmedia.com

'Nobody else does this': Why Carney's fiscal anchors are raising questions about Canada's financial credibility

2025-12-03 15:04:33